The Silent Trap: When Good Marks Hide Weak Learning Habits

When Comfortable Results Quietly Delay Real Problems

Most Malaysian parents know this feeling well.

The report card arrives. The marks look good. Teachers’ comments are neutral or encouraging. There are no urgent messages, no red flags, no calls to “please see me”.

So we relax.

But in reality, some of the most serious learning problems don’t appear when results are poor. They appear when results are comfortably good.

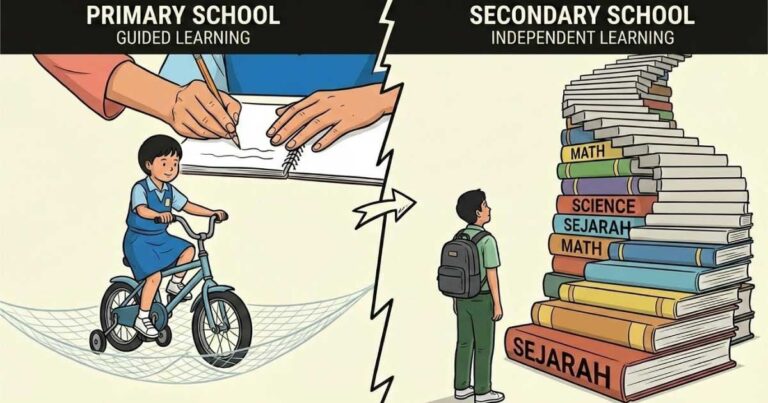

At Zekolah, we often see students from SJKC, SMK, and CIS(Chinese Independent school) backgrounds whose marks remain strong for years — until they suddenly collapse. It is only when the syllabus shifts — such as the jump from Standard 3 to 4, or the difficult transition to secondary school — that the system stops compensating. Parents feel blindsided. Students lose confidence almost overnight.

What’s really happening is simpler, and more worrying:

learning habits were weakening quietly, while the system kept compensating.

Performance vs Learning: Why Marks Don’t Tell the Full Story

To understand this pattern, we need to separate two ideas that are often treated as the same.

Performance is the ability to produce the correct answer at a specific moment, usually during an exam.

Learning is a lasting understanding that can be applied again, in a new situation, without guidance.

A student can perform well without learning deeply.

A very common example appears in Bahasa Melayu writing. A child memorises an essay template word-for-word for an exam. During the test, they reproduce it accurately and score an “A”. On paper, this looks like strong language ability.

But ask the same child to write a short paragraph on a different topic a week later, and they struggle to form sentences independently. The exam performance was strong, but the language mechanics were never truly learned.

This reliance on short-term memory, spotting questions, or rigid template memorisation creates what educators often call hollow achievement. The foundation looks solid from the outside, but it cannot support more complex demands later.

Why Good Marks Are Often Misleading in the Early Years

In lower primary and early upper primary, the system quietly absorbs weak habits.

Homework is frequently corrected or guided by adults, which is often exactly the problem explained in Homework Isn’t the Problem — Dependency Is. Tuition lessons often focus on showing the “safe” method or expected answer rather than building reasoning. Exams reward familiarity, repetition, and recall more than explanation or application.

As long as question types stay predictable, students survive — and sometimes excel — using these strategies. Parents see good results and naturally assume understanding.

Nothing looks broken, so nothing gets fixed.

The Weak Learning Habits That Stay Hidden

The most dangerous habits are not obvious. In fact, they often look like diligence.

Some students study only when told. They complete tasks under supervision but struggle to initiate or plan learning independently. Others depend heavily on model answers, memorising structures instead of constructing meaning.

Another common pattern is memorising without understanding. These students can follow steps but cannot explain why those steps work. When a question changes slightly, or when ideas must be connected across chapters, their confidence disappears.

Avoidance usually follows. Unfamiliar questions are skipped or rushed — not because the student is lazy, but because they have never practised thinking beyond fixed patterns.

One clear warning sign is the “Last-Minute Sprint.” Some students coast through the term doing the bare minimum, then pull several sleepless nights just before the exam to secure an “A.” While this strategy can sometimes work in lower primary years, where facts are limited, it becomes risky in upper primary and secondary assessments like UASA or SPM, which demand cumulative understanding and reasoning.

Why the Decline Feels “Sudden”

Parents often say,

“He was doing fine last year. This year everything fell apart.”

What changed was not effort. It was demand.

Upper primary and secondary assessments increasingly require students to explain reasoning, solve multi-step problems, and apply knowledge across topics. KBAT-style thinking becomes normal, not optional. At this stage, memorisation stops carrying the same weight. Familiar templates disappear. The system stops compensating.

The danger of hidden weak habits is that they work — until they don’t. Typically, we see the “crash” occur when the complexity of the subject outpaces a student’s ability to memorize.

In Malaysia, this is increasingly common with the shift toward ongoing assessment (PBD) and UASA. The Ministry of Education is moving away from rote memorization toward analytical thinking. A student who has coasted on memorising keywords or relying on excessive tuition hand-holding can suddenly hit a wall. The tragedy is that because their grades were strong for so long, neither the parent nor the student notices the problem building. The drop is often blamed on a “hard paper” or a “bad teacher,” rather than years of accumulated learning debt.

The Warning Signs That Matter More Than Marks

Instead of waiting for grades to fall, pay attention to these signals. They point to a breakdown in thinking, not effort:

- Avoidance when questions look unfamiliar

- Panic during tests despite preparation

- Statements like, “I studied, but I don’t know why my answer is wrong”

What Parents Can Do Instead

The most effective shift is moving from checking answers to examining process. Ask your child to explain their reasoning. Change a question slightly and see if they can adapt. Notice whether they can apply ideas across topics without prompts.

This is where purposeful practice becomes important. Rather than waiting for exams to reveal learning gaps, parents can use structured exercises to see how their child thinks independently.

- For Standard 4 students, Zekolah’s Textbook-Aligned Exercises help strengthen core skills and build independent learning habits after the jump from Standard 3.

- For Standard 5 students, Past Year Papers provide practice with more complex problems and reveal weak habits before upper primary assessments.

- For Standard 6 students, exam-style exercises prepare them for upper primary and secondary assessments like UASA, ensuring their learning habits are solid before the transition.

By using the right materials at each level, parents can guide learning without doing the work for their child. When a student attempts realistic exam questions without heavy guidance, parents can see whether concepts are understood, or if unfamiliar question formats trigger panic. Diagnosis builds confidence. Pressure erodes it.

What Marks Can — and Cannot — Tell You

Good marks tell you what a child can produce — not how they got there.

Celebrate results, but don’t stop there. Sustainable success comes from habits that survive changing exam demands. Look beyond the numbers. That’s where real learning begins.